Legendary artist and scientist Leonardo da Vinci, who conducted the first systematic study of friction, has always been credited as the pioneer in Tribology. But while his famous machinery design sketches reflected the inventor’s knowledge of the benefits and drawbacks of friction, precisely when and how Leonardo developed these ideas, has remained a mystery.

Now, a detailed study conducted by University of Cambridge Professor Ian Hutchings, has revealed that Leonardo had acquired a sophisticated understanding of the laws of friction in 1493 — almost 200 years before they were formalized! What’s stunning is that the evidence, contained in a tiny 92 mm x 63 mm (3.6 x 2.5 in) notebook, was overlooked, despite being on public display at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum for over a century.

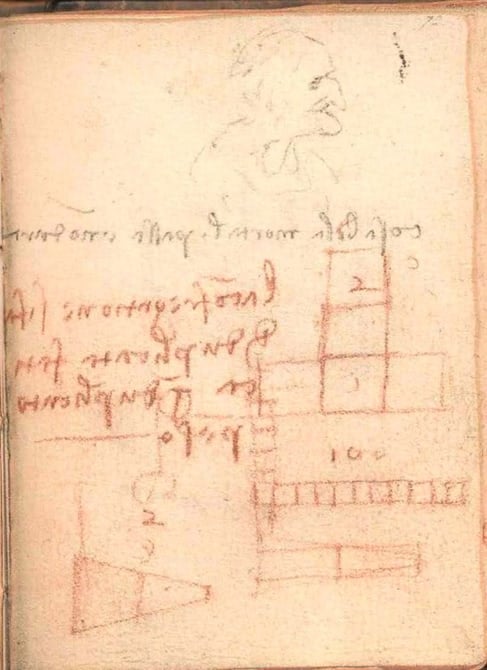

That’s because the artist had outlined his groundbreaking research on the same page as a sketch of a woman thought to be an older version of Helen of Troy. Hence, while experts spent years debating the significance of the image and its accompanying phrase, “Cosa Bella mortal passa e non dura,” (“mortal beauty passes and does not last”), they paid little attention to the scribbles below. In the 1920’s, the museum director even went as far as labeling the information as "irrelevant notes and diagrams in red chalk."

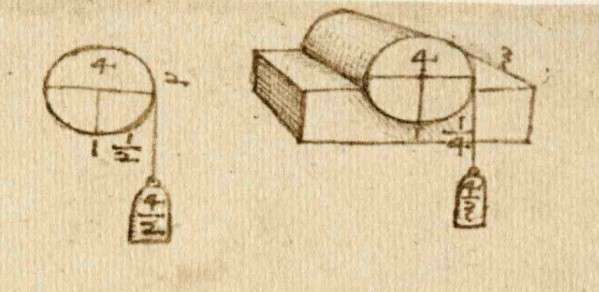

It was not until Hutchings decided to create a detailed chronology of the brilliant scientist’s studies of friction that he realized the “irrelevant” scribbles were a critical component of Leonardo’s ideas and perhaps even the “aha!” moment of his work with friction. The red chalk writing and images, sketched in Leonardo’s characteristic “mirror writing” from right to left, depict rows of blocks being pulled by a weight hanging over a pulley. If that sounds familiar, it is because it is similar to the experiment conducted in classrooms today to demonstrate the laws of friction.

Hutchings, who published his findings in the scientific journal Wear, in July, says, “The sketches and text show Leonardo understood the fundamentals of friction in 1493. He knew that the force of friction acting between two sliding surfaces is proportional to the load pressing the surfaces together and that friction is independent of the apparent area of contact between the two surfaces.”

Before this, the discovery of the rules of friction was credited to 18th century French scientist, Guillaume Amontons. Researchers say Hutchings’ findings do not mean Guillaume stole Leonardo’s ideas or that he was even was aware of them. It just confirms that Leonardo had figured out the fundamentals of Tribology almost 200 years before the rest of us, making him the true pioneer in the subject.

Resources: newatlas.com, phys.org,collective-evolution.com