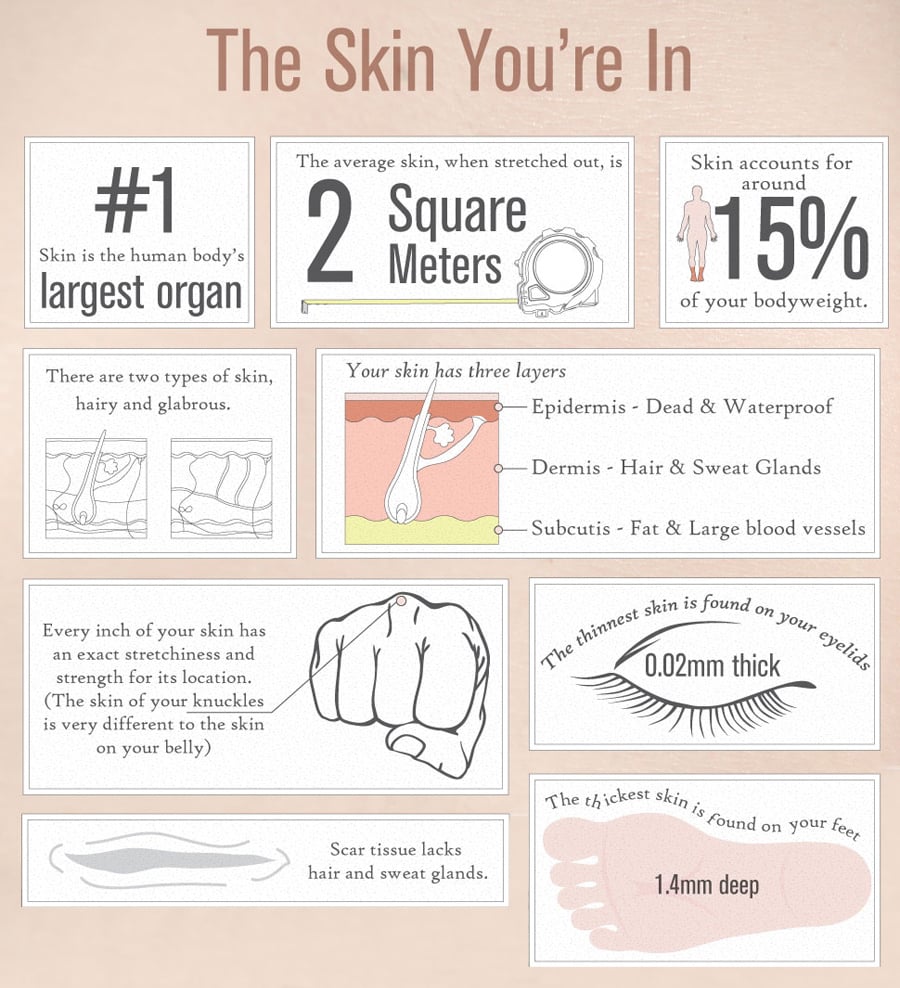

Scientists have long maintained that the skin, which makes up roughly 15 percent of a person’s body mass, is the largest organ in the human body. However, now researchers from New York University's School of Medicine appear to have stumbled upon what they believe may be an even larger organ. Called the interstitium, it is not solid like the heart or liver, but a network of fluid-filled spaces that is present throughout the body to protect the rest of our organs.

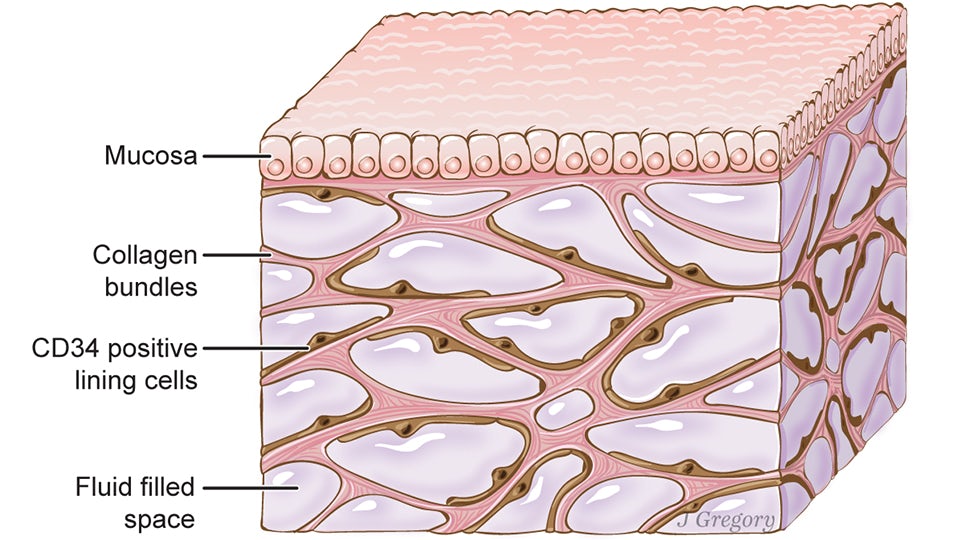

According to team leader Dr. Neil Theise, the massive organ, which has been hiding in plain sight, was overlooked because the human tissue is currently studied by treating the thinly-sliced cell samples with chemicals. The technique, which drains the fluid from the tissue and destroys its collagen structure, led the experts to classify the interstitium as just a dense connective tissue.

However, when Theise’s team viewed a patient’s bile duct with a new kind of endoscope that allowed them to observe frozen living tissues at a microscopic level, they made an intriguing discovery. Instead of being a dense connective tissue, the interstitium, found everywhere — under the surface of the skin, surrounding internal organs, and even wrapped around veins and arteries — is a mesh of fluid-filled structures supported by strong, flexible proteins.

"We would often see little ‘cracks’ between collagen bundles in these layers," said Theise. "I was taught, and in turn taught many of my trainees, that these cracks were artifacts of processing. We had pulled the tissue too hard in preparing the slide and separations had formed. But these were not artifacts: these were the remnants of the collapsed spaces. They had been there all the time. But it was only when we could look at living tissue that we could see that."

The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports on March 27, 2018, asserts that the interstitium’s flexible protective wall allows organs to conduct pressurized functions without breaking down over time. The researchers theorize that since the fluid in the interstitium feeds into the lymphatic system, it might provide an answer to how cancer cells spread so rapidly during metastasis.

However, some experts are not ready to accept the interstitium’s newly-elevated status. "I would think of this as a new component that is common among a variety of organs, rather than a new organ in and of itself. It would be analogous to discovering blood vessels for the first time, in that they are in every organ, but they aren't an organ themselves," said Dr. Michael Nathanson, professor of medicine and cell biology at Yale University School of Medicine. Regardless of the classification, the discovery will help scientists find new ways to cure deadly diseases, like cancer, which claim millions of lives annually.

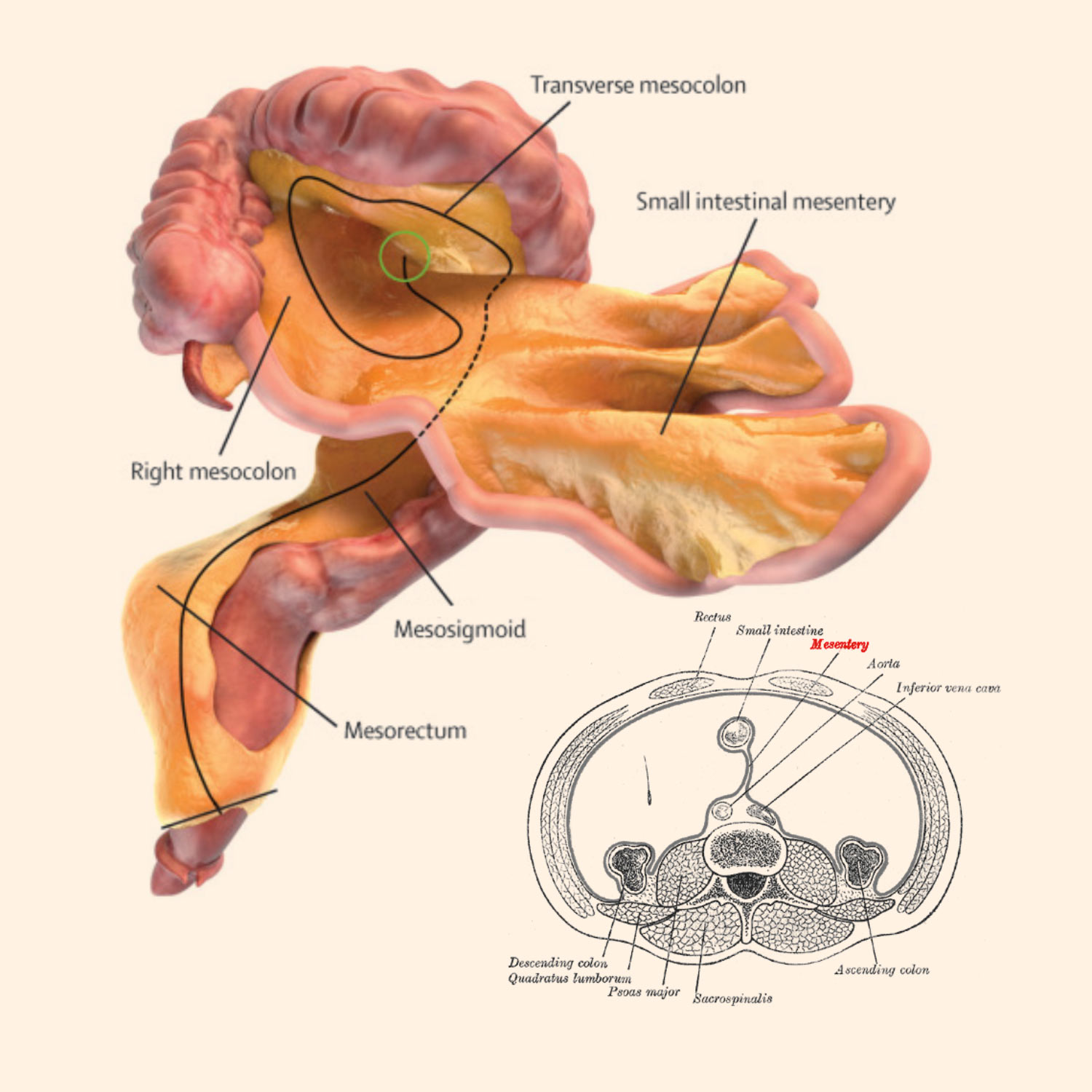

This is not the only new “organ” discovery. In January 2017, a team led by J. Calvin Coffey, from the University Hospital Limerick in Ireland, upgraded the mesentery, which connects our intestines to the abdominal wall, to an organ. Their conclusion was based on the fact that the mesentery was not a mishmash of fragmented and disparate structures as had been previously believed, but one continuous piece.

Resources: eurakaalret.org, chicagotribune.com,newatlas.com