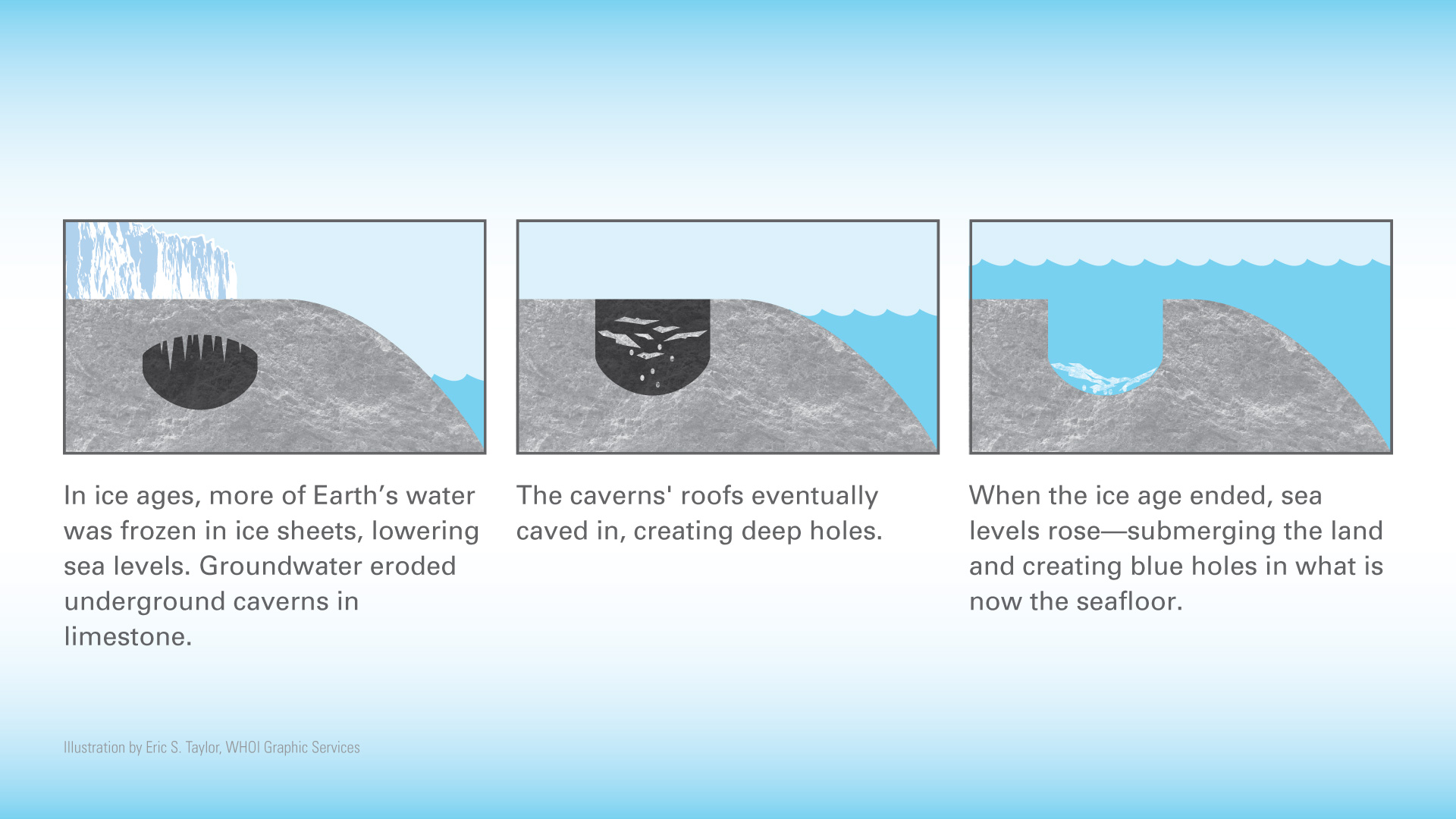

Scattered across the ocean bed, and often hidden from the human eye, are hundreds, or perhaps even thousands, of "blue holes." The massive underwater sinkholes, which host a diverse biological community — ranging from coral to sponges to sharks to sea turtles — were formed thousands of years ago when groundwater dissolved karst, a type of porous limestone rock found on ocean floors.

The intriguing caverns, which are a favorite among deep-sea divers, have never been fully explored by scientists, because they are hard to detect and reach, and the opening of many blue holes is too narrow to lower automated submersibles. However, that may change soon thanks to a series of missions that the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is sponsoring to explore a mysterious blue hole off Florida's Gulf Coast. Dubbed "Green Banana," the 425-foot-deep submarine cave lies 155 feet below the ocean's surface about 50 miles offshore from St. Petersburg.

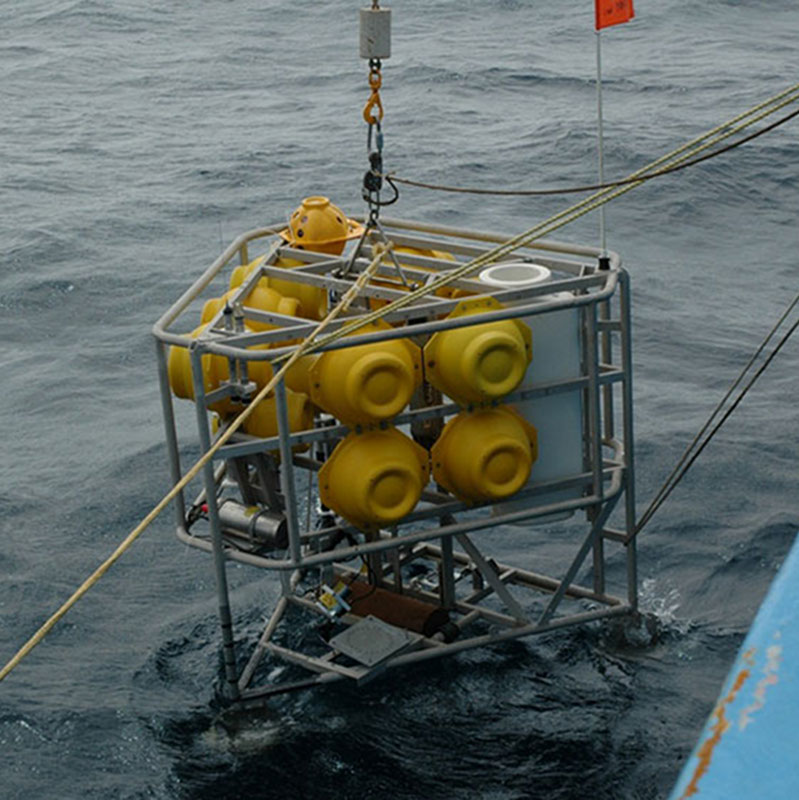

The researchers, from Mote Marine Laboratory, Florida Atlantic University, Georgia Institute of Technology, and the US Geological Survey, will make their inaugural attempt to reach the bottom of the deep cavern in August 2020 using a benthic lander. The autonomous, triangular-prism-shaped exploration equipment will remain inside the hole for 24 hours, collecting sediment and water samples. It will also record the water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, clarity, and bottom currents every 15 minutes.

Human divers will also explore the blue hole, albeit for shorter periods of time. Dr. Emily Hall, a scientist and program manager at Mote Marine Laboratory, who is certified to dive up to 200 feet, will conduct water and biological sampling close to the rim. Meanwhile, a team of technical divers, including Jim Cutler, a senior scientist and program manager at the Mote Marine Laboratory, will attempt to dive all the way to the bottom to collect specimens from the cavern's base.

The endeavor, which requires specialized training as well as rigorous health checks, is not without risk. "As you go deeper and stay longer, you have to worry about decompression illness. That happens when you accumulate too much nitrogen in your body tissues, then you have to come up slowly so that the nitrogen doesn't try to bubble out of your blood," Cutler told CNN. "For divers going to the bottom of 'Green Banana,' over 400 feet, that might take closer to two hours."

Also of concern is the blood's oxygen level, which needs to be lower than that on the ground to prevent toxic effects, which can lead to seizures. "The way we get around it is we change what we are breathing," Cutler said. "This is done by adding helium to the mix of air in the tank, which tends to reduce oxygen toxicity."

The Green Banana's hour-glass shape, which has a restriction about mid-way down, will pose an additional challenge to the already arduous mission. "It's going to make it pretty difficult to get some of the equipment and some of the teams down into the bottom of the hole, but we're working really hard on trying to come up with the best way to strategically do that and keep everyone safe," Hall told CNN.

This is not Cutler's first foray inside a blue hole. In 2019, the researcher led a team of divers to the bottom of the 237-foot-deep Amberjack Hole, about 30 miles offshore from Sarasota, Florida. An analysis of the specimens collected showed large amounts of dissolved inorganic carbon, both in the water and sand, leading the researchers to believe the blue holes may be capable of supporting some kinds of microbial life.

The team also found evidence of nutrients emerging from the blue hole, which they believe may explain the abundance of plants and animals, in the otherwise barren seafloor. Though the bottom of the hole did not house any living marine animals the scientists did find two perfectly preserved specimens of the endangered smalltooth sawfish.

Whether the Green Banana investigation yields similar results remains to be seen. "One of the things that I really love about this mission is that it is exploratory research. We don't know what we're going to find," Hall told CNN.

Though Green Banana is one of the deepest-known blue holes, it is not the deepest one ever found. That honor belongs to the Sansha Yongle Blue Hole in the South China Sea that reaches down an astounding 984 feet (300 meters). To put it in perspective, that is deep enough to submerge France's iconic Eiffel Tower!

Resources: CNN.com, oceanexplorer.noaa.gov.