Despite technological advances, modern concrete structures start to crumble in just 50 years if not maintained. This contrasts sharply with Italian monuments that remain standing after over 2,000 years. Now, an international research team has finally uncovered how Roman concrete wonders continue to survive to this day.

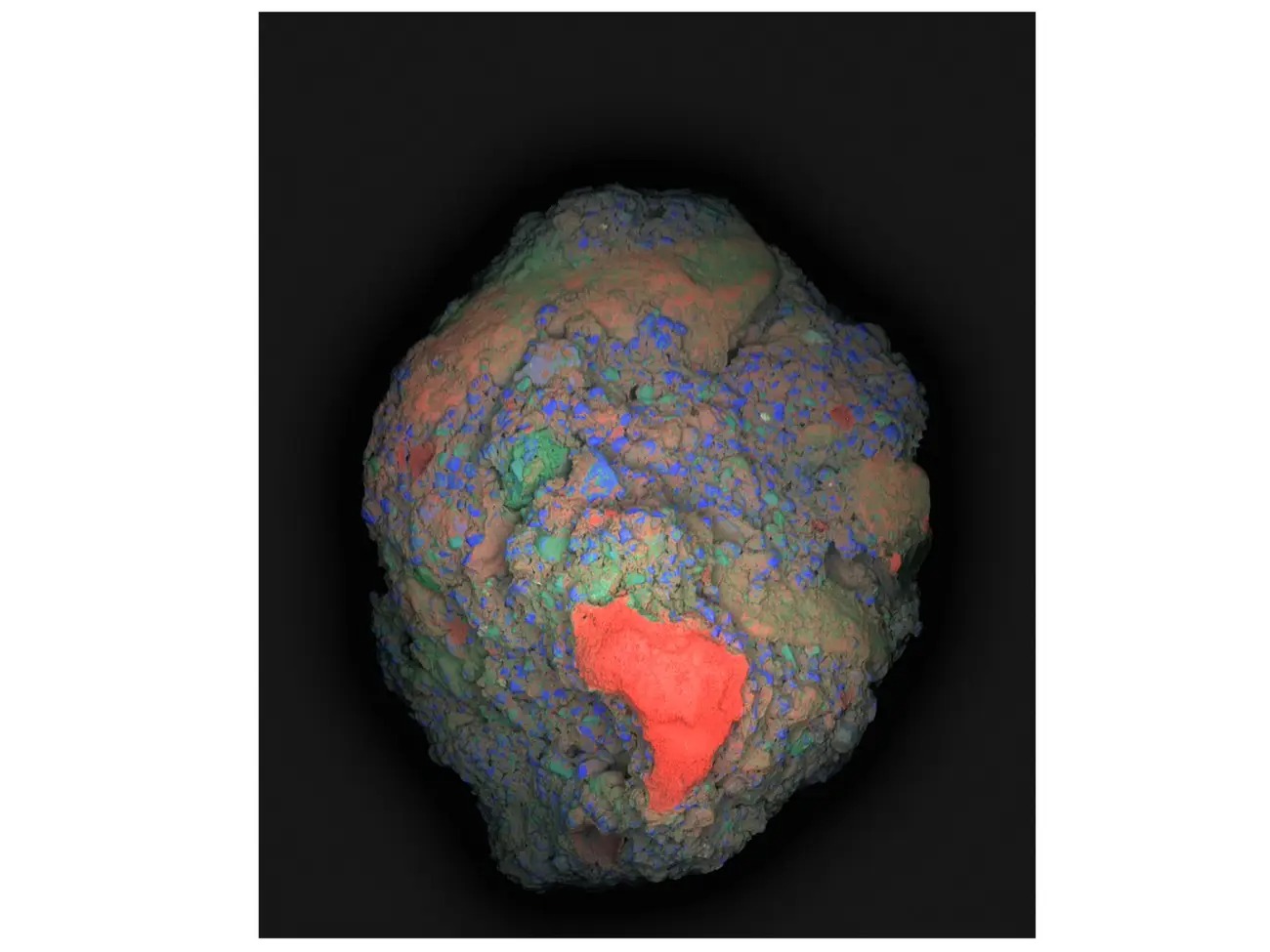

According to team leader Dr. Admir Masic, the secret lies in tiny clumps known as lime casts. They have been found between the concrete in all ancient Roman construction. Researchers had always believed the clumps were a result of "sloppy mixing." But the engineering professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suspected they served a purpose.

"If the Romans put so much effort into making an outstanding construction material, why would they put so little effort into ensuring the production of a well-mixed final product?" said Masic. "There has to be more to this story."

Upon closer examination, the researchers found that the lime casts were a form of limestone known as quicklime. The brittle material is produced by heating crushed limestone at high temperatures. The scientists theorized that as cracks appear in the concrete, the quicklime crumbles. It fills the tiny areas between the cracks. When water flows through the gaps, it reacts with the quicklime to form limestone. The hardened mineral plugs any cracks in the concrete.

The team tested their theory by running water through cracks in two concrete blocks. Only one contained quicklime. Sure enough, within two weeks, the water stopped seeping through the concrete containing quicklime. However, water continued to flow freely through the concrete without the quicklime.

Masic and his team published their findings in the journal Science Advances on January 6, 2023. They hope their discovery will help improve the longevity of modern concrete structures.

Resources: Businessinsider.com, Newatlas.com, news.mit.edu